Unlock the potential of modern distributed systems with our latest exploration: The Transactional Outbox Pattern. Discover how this pattern enhances data consistency, reliability, and system resilience in microservices architectures.

Introduction: Navigating the Complexities of Modern Software Development

In the realm of software development, managing data consistency and integrity is a cornerstone of reliable systems. The complexity escalates when we transition from a single, well-understood system to an interconnected web of services and components.

The simplicity and robustness of SQL databases have long been a foundation in software development. These databases offer ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) properties, ensuring transactions are processed reliably. In this controlled environment, developers can perform business logic within transactions confidently, knowing that any failure will trigger a rollback, preserving data integrity and preventing inconsistent states. This traditional model has proven effective and straightforward when operations are confined within the bounds of a single database.

However, modern software architectures often require interactions beyond a single database. The introduction of third-party systems and external services adds layers of complexity when business logic involves modifying data across distributed systems, such as a SQL database and a event bus like RabbitMQ. In these distributed architectures, the ACID properties, which are the backbone of transactional integrity within a single database, become challenging to enforce across multiple systems.

One of the core issues is the uncertainty of atomicity. For instance, consider a scenario where a transaction involves writing an event to a RabbitMQ and also updating a record in a database. There’s a possibility that the event write to RabbitMQ succeeds, but the outer database transaction fails. This results in a scenario where an event indicating a business action is published, but the corresponding database state does not reflect this action because the transaction was not completed successfully. The system thus ends up in an inconsistent state, with the event bus reflecting a change that the database does not.

When integrating an event bus or any other external service within an application in a distributed system, there are two naive approaches one might consider. Each approach has its own set of challenges and potential pitfalls:

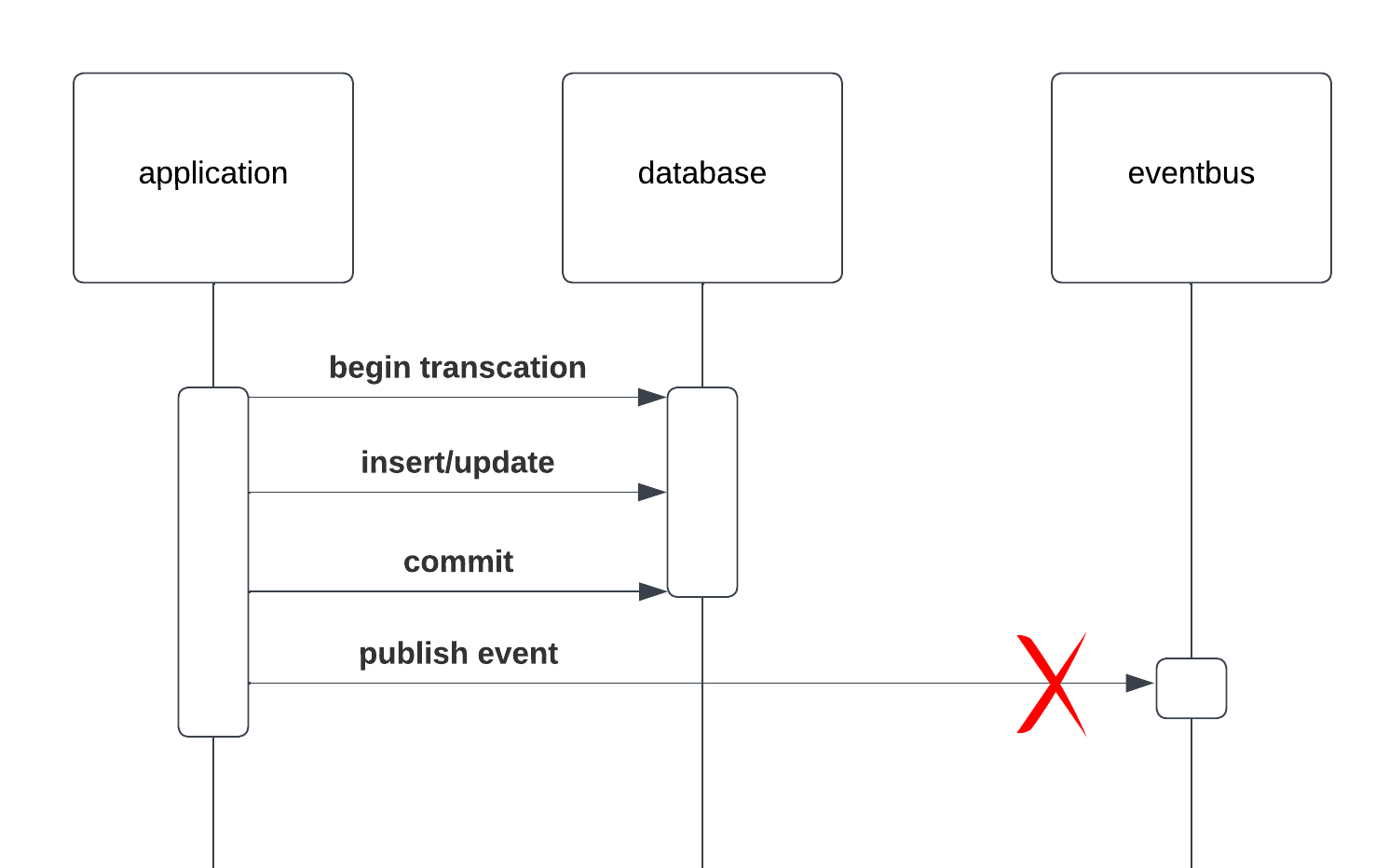

1. Execute Business Logic Within the Transaction and Publish Events After Committing the Transaction

In this approach, the application first executes all the required business logic within a database transaction. After this transaction is successfully committed, it then publishes the relevant events to the event bus.

Challenges:

- Risk of Event Loss: If the application crashes or encounters an issue between the transaction commit and the event publication, the event may never get published. This leads to a situation where the database state has changed, but the corresponding event informing other services of this change is lost.

- Inconsistency in Distributed Systems: Other services relying on these events for triggering their own processes will not be aware of the changes, leading to data inconsistency across the system.

- Complex Recovery Mechanisms: Implementing a mechanism to check for such failures and recover from them can be complex and error-prone.

This approach can be suitable for situations where the events being published are not critical to the core business logic or data integrity of the application. An example of this might be events used for monitoring or logging purposes. In these cases, the loss of some events due to system failures or crashes might be considered an acceptable risk.

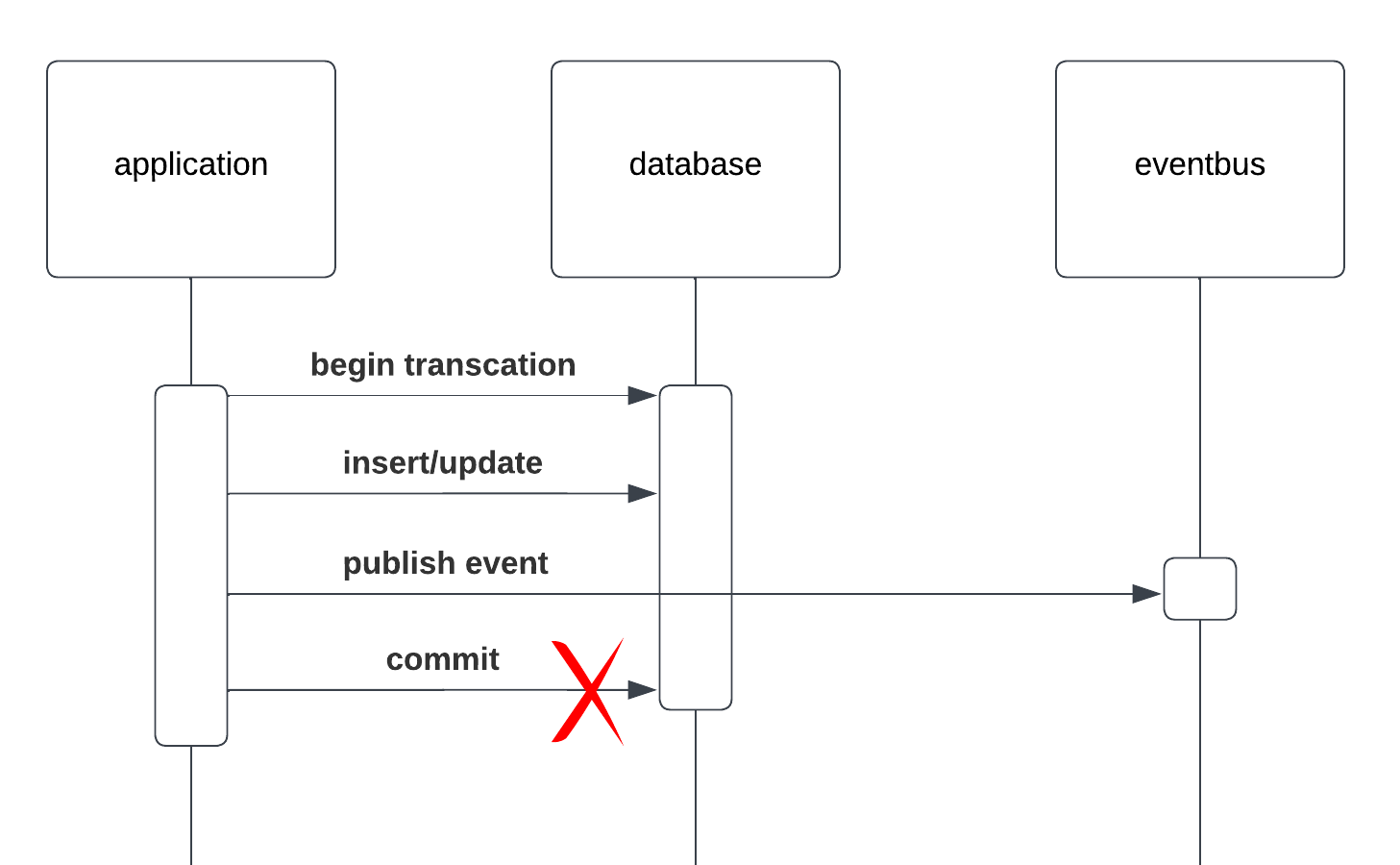

2. Execute Business Logic and Publish Events Within the Transaction

In this approach, the application attempts to execute business logic and publish events to the event bus, all within the same database transaction.

Challenges:

- Event Publication Preceding Transaction Commit: When events are published to the event bus as part of the database transaction, there’s a risk that the transaction might not successfully commit even after the event has been sent out. This situation can occur due to various reasons, such as issues in completing subsequent operations within the same transaction or a late-occurring failure in the database.

- Inconsistent State Risks: If the transaction fails to commit after the event is published, it leads to a critical inconsistency. The event bus carries an event that suggests a change or action that, in reality, the database did not finalize. This discrepancy can lead to serious data integrity issues, as other services responding to the event may act on data that doesn’t accurately reflect the current state of the system.

- Complex Error Handling: The application must be prepared to handle these scenarios, where the event is out in the world, but the corresponding transaction failed. This requires sophisticated error handling and potentially complex rollback mechanisms, not just for the database changes, but also for any actions taken by services that consumed the premature event.

In the past, one common approach to address such issues was through distributed transactions, like the two-phase commit (2PC) protocol. 2PC was designed to ensure atomicity across multiple database systems, attempting to maintain data consistency by coordinating a commit or rollback across all involved systems. However, this approach comes with significant drawbacks, particularly in distributed and microservice-based architectures:

- Performance Overhead: The 2PC protocol is known for being resource-intensive and can significantly impact system performance, particularly in high-throughput environments.

- Complexity and Scalability Issues: Managing and coordinating distributed transactions across multiple systems adds a layer of complexity and can become a bottleneck in scalable systems.

- Lack of Support in Modern Ecosystems: Many modern message buses and RESTful APIs do not support the 2PC protocol, making it challenging to implement in contemporary microservices architectures.

The Real-World Implications of Naive Approaches

From a theoretical standpoint, the challenges with these naive approaches in integrating an event bus within an application may seem obvious. However, drawing from my professional experience across various projects, I have observed these issues manifest repeatedly in real-world scenarios. Whether it’s dealing with distributed systems employing message buses, interacting with external systems through REST APIs, or managing multiple databases, a common error persists: a lack of clarity among developers regarding the consistency semantics of their applications.

In practice, this oversight leads to perplexing and hard-to-diagnose errors. Developers often underestimate the complexity introduced by distributed environments and might not fully consider the implications of their chosen implementation strategy. As a result, applications can exhibit erratic behavior, where the root cause is deeply embedded in the flawed interaction between different system components. These issues can be especially challenging to debug and resolve, given the distributed nature of these systems and the often subtle interdependencies between their components.

The crux of the problem lies in the assumption that techniques and patterns used in monolithic or single-database applications can be directly applied to distributed systems. This misconception overlooks the fundamental differences in how distributed systems handle data consistency and transaction management. The consequences of this oversight are not just theoretical inconsistencies but tangible bugs and system failures that can have a significant impact on the reliability and integrity of the application.

This challenge highlights the inherent difficulty in ensuring atomicity and consistency when dealing with internal transactions and external communication within the same operational scope. It underlines the necessity for a pattern like the Transactional Outbox, which offers a way to decouple these concerns, ensuring that events are only published after the transaction’s successful commitment, thereby maintaining the integrity and consistency of the overall system.

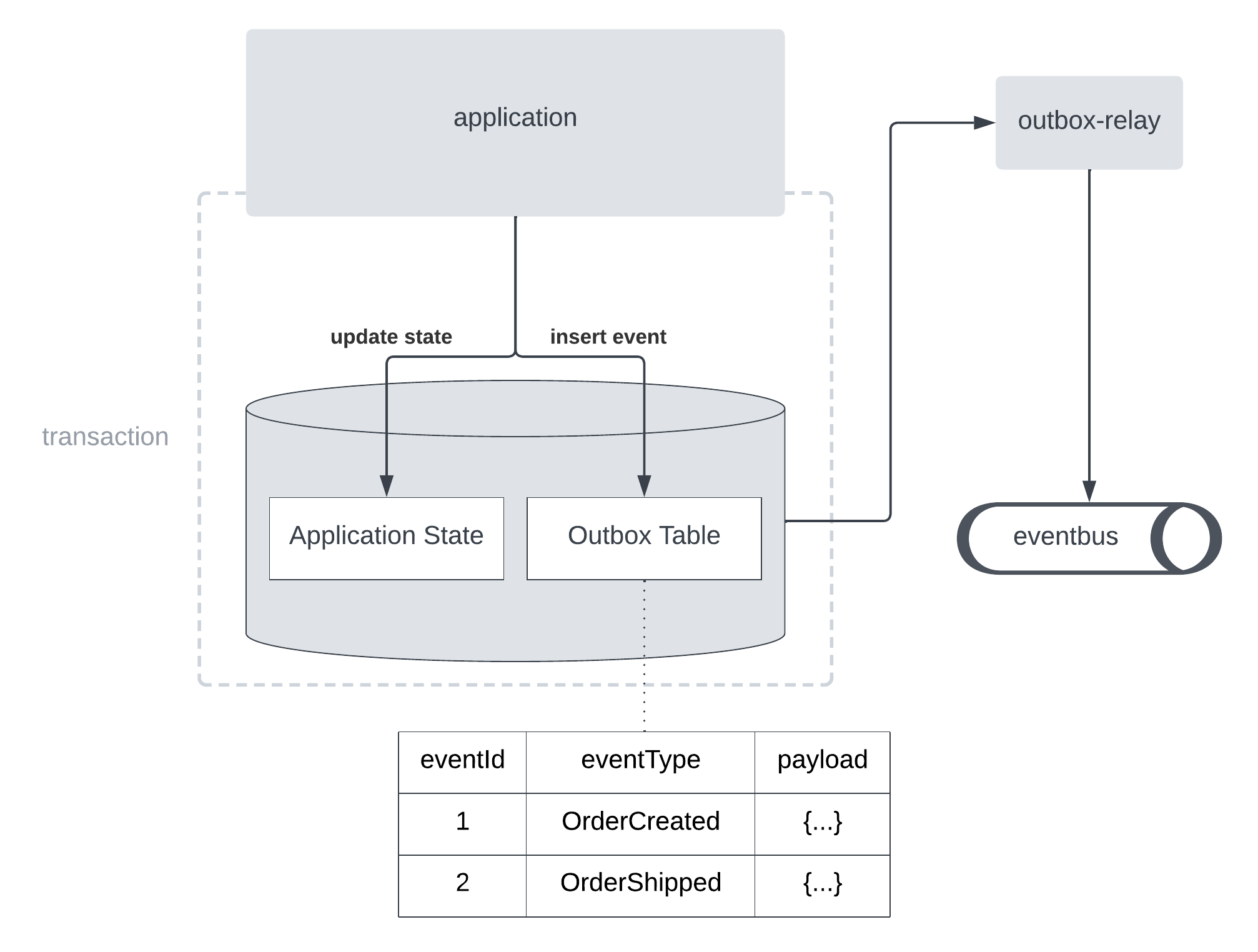

Understanding the Transactional Outbox

The Transactional Outbox is a design pattern used in microservices architectures to ensure consistent and reliable message publishing in distributed systems. At its core, the pattern solves a fundamental problem: how to update a database and publish messages/events to a message bus or event-driven system and keep the state consistent.

How It Works

- Local Transaction with Outbox Table: Instead of directly publishing an event to the message bus, the application writes the event into a special table within the same database as part of the business logic transaction. This table is commonly referred to as the outbox.

- Atomic Commit: The key to this pattern is the atomic commit. The changes to the business data and the insertion of the event into the outbox are done in the same database transaction. This ensures that either both are committed or neither, maintaining the atomic nature of operations.

- Reliable Event Publishing: After the transaction commits, a separate process (which could be a service, a scheduled job, or a database trigger) reliably reads events from the outbox and publishes them to the message bus. This process ensures that each event is eventually published without being lost.

- Event Deletion/Mark as Processed: Once the event is successfully published to the message bus, it is either deleted from the outbox or marked as processed, preventing it from being published again.

By using the transactional outbox, the application ensures that the state in the database and the published events are always consistent. Moreover, the pattern exhibits a remarkable resilience to system failures. If the application crashes after committing the transaction but before the event is published, the separate process ensures that the event will still be published later. Another significant advantage of the Transactional Outbox Pattern is the decoupling it offers. By separating the concerns of database transactions and event publishing, the pattern allows each to operate independently. This separation not only simplifies the architecture but also enhances scalability and maintainability. It allows the system to evolve more flexibly, adapting to changes and scaling components independently without disrupting the fundamental operations of transaction management and event distribution.

Additionally, an often overlooked yet significant aspect of the Transactional Outbox Pattern is its efficiency, particularly regarding the speed of writing to the outbox. Writing an event to the outbox involves merely appending a row to a table, which is one of the fastest operations in database management. This efficiency means that the pattern does not impose a notable performance penalty.

Challenges and Solutions

Implementing the Transactional Outbox Pattern, while beneficial, brings its own set of challenges that need careful consideration and handling.

At least once delivery

When implementing the Transactional Outbox Pattern in a distributed system, it’s important to understand that this pattern inherently guarantees at-least-once-delivery semantics. At-least-once-delivery is a delivery approach where the system ensures that a message is definitely delivered to its destination at least once. Since the delivery mechanism is designed to ensure that messages are not lost, it errs on the side of sending duplicates rather than risking a message not being delivered at all. As a result, the receiving services or components must be equipped to identify and appropriately handle these duplicate messages. This involves implementing logic to detect if a message has already been processed and ensuring that processing it again does not adversely affect the system’s state or lead to incorrect operations.

A common approach to handle duplicate messages is implementing idempotency at the technical level. This involves recording the IDs of consumed events and checking against this record before processing new events. If an incoming event’s ID matches one that has already been processed, it is ignored, thus preventing duplicate processing.

A more sophisticated approach is to design idempotency based on business rules. Instead of just tracking event IDs, this approach involves designing the business logic and data models in such a way that repeating the same operation does not have adverse effects. For example, applying the same update twice would result in the same state as applying it once. This method requires a deeper understanding of the business context but can lead to a more robust solution.

Consider the process of stock reservation in a warehouse. In this scenario, every time an item is reserved for a shipping order, the system communicates not just the quantity reserved, but also the remaining quantity in stock. When an article is reserved, the system sends an update that includes both the number of pieces reserved and the current stock level. This comprehensive update provides a complete picture of the stock status after each transaction. With the detailed stock information at hand, a replenishment component in the system can easily apply business rules to monitor stock levels. For instance, if the system receives multiple updates about the same reservation due to a duplicate message, it can discern that the stock level hasn’t further decreased since the quantity and remaining stock are consistently reported. By structuring the update messages in this way, applying the same stock reservation update more than once does not lead to incorrect stock calculations. The system remains aware of the actual stock level, regardless of duplicate messages, ensuring that replenishment decisions are based on accurate and current information.

Eventual Consistency

Eventual consistency refers to a model where the state of the system is not immediately synchronized across all its components following a change. Instead, these changes propagate through the system over time, resulting in a lag during which different services might have different views of the system’s state. Eventually, however, all services reach a consistent state, hence the term “eventual consistency.” This concept contrasts with “strong consistency,” where a system ensures immediate consistency across all nodes after any operation.

In the realm of distributed systems, particularly those transitioning from traditional SQL database architectures, the concept of eventual consistency often poses a significant mental shift for developers. Accustomed to the strong consistency guarantees of SQL databases, where the recent write operation is immediately visible to all subsequent read operations, developers may find the notion of eventual consistency unsettling. This model, where data is not immediately consistent across all services of the system but becomes consistent over time, can seem counterintuitive and raise concerns about data integrity and application behavior.

In discussing the eventual consistency inherent in the Transactional Outbox Pattern, it’s important to clarify a common misconception: the introduction of the Transactional Outbox Pattern does not, in itself, bring about eventual consistency in a system. Rather, if your system already incorporates an event bus, it is by design operating under the principles of eventual consistency.

The nature of an event bus in a distributed architecture inherently implies that there’s a delay between when an event is generated and when it is received and processed by other parts of the system. When an event is published to the bus, it doesn’t instantly synchronize the state across all services and components. Instead, these components update their state as and when they process the event, leading to a period during which different parts of the system may have slightly different views of the overall state.

However, a closer examination of real-world processes reveals that eventual consistency is not only natural but often the norm. Consider the example of ordering a meal in a restaurant:

- Ordering Process: When you place an order with the waiter, there’s no immediate check with the kitchen to confirm if every ingredient is available. The waiter takes orders from multiple tables, and only later are these orders processed by the kitchen.

- Handling Unavailability: If an ingredient is unavailable, the waiter informs you later, and you’re given the option to choose an alternative. This delay in information and the need to adapt is a classic example of eventual consistency at play.

The same principle applies to many everyday business processes:

- Hotel Bookings: When you book a hotel room online, there’s often a delay before the booking is confirmed. During high-demand periods, you might even receive a notification later that the room is no longer available, prompting you to find an alternative.

- Online Shopping: Shopping on platforms like Amazon involves a period where the order is processed, and only later do you get confirmation. In some cases, you might be notified of out-of-stock items or shipping delays.

- Flight Bookings: Booking a flight doesn’t guarantee a seat until various checks are completed, and occasionally, overbookings lead to last-minute changes.

Just as these real-world scenarios adapt and manage eventual consistency, applications in distributed systems must be designed to handle it gracefully. It’s essential to recognize that eventual consistency is not a flaw but a characteristic of distributed systems that, when properly managed, can lead to greater scalability and resilience. Applications should be designed to expect and handle delays in data synchronization and to manage the exceptions that arise when things don’t go as expected.

Developers can draw lessons from these real-world analogies to better understand and implement eventual consistency in their systems. By acknowledging that not all processes require or benefit from strong consistency, and by designing systems that can handle inconsistencies and adapt as needed, developers can build more robust, flexible, and scalable applications. This mindset shift is crucial in successfully navigating the complexities of modern distributed systems.

Hands-On Guide: Implementing the Transactional Outbox Pattern with Spring Boot and RabbitMQ

We will demonstrate how to implement the Transactional Outbox Pattern in a Spring Boot application, integrated with RabbitMQ for message handling. For the transactional outbox mechanism, we’ll utilize the Transaction Outbox library, a well-curated Java library that offers seamless integration with Spring Boot and other frameworks like Quarkus.

The sample project provides an REST endpoint for creating user profiles.

Upon creating a user, it publishes a UserCreatedEvent to RabbitMQ, demonstrating the Transactional Outbox Pattern’s capabilities.

1. Cloning the Repository

Our example project repository is available at SWCode Samples on GitHub. This repository provides a “plug and play” setup with a docker-compose file that includes a PostgreSQL database and a RabbitMQ container, offering a hassle-free way to get the environment up and running.

git clone https://github.com/sw-code/swcode-samples.git

cd swcode-samples/transactional-outbox

Running Application

- Starting the Application: Use Docker to start the PostgreSQL and RabbitMQ services

docker-comose up, and then run the Spring Boot application. - Creating Users: To test user creation and the subsequent event publishing, you can use the

/usersendpoint. This will trigger the flow from the user creation in theUserServiceto the publishing and handling of theUserCreatedEvent. - Observing Event Handling: As you create users through the endpoint, keep an eye on the logs of the RabbitMqConsumer.

You should see the

UserCreatedEventpayloads being logged, indicating that the events are successfully being consumed from RabbitMQ.

For convenience, the repository includes a sample-requests.http file,

which provides easy access to all the endpoints if you are using IntelliJ IDEA.

This file simplifies the process of making requests to the application for testing purposes.

Explore the Code

The UserController controller provides an endpoint to create users.

@PostMapping("/users")

fun createUser(@RequestBody request: UserCreateRequestDto): User {

return userService.createUser(request.name)

}

When a user is created, a UserCreatedEvent is published.

This is done using the OutboxPublisher to persist the event in the outbox first, and then forward it to RabbitMQ.

class UserService(

private val userRepository: UserRepository,

private val eventPublisher: EventPublisher) {

fun createUser(name: String): User {

return userRepository.save(User(UUID.randomUUID(), name)).also {

eventPublisher.publish(UserCreatedEvent(it.id, it.name))

}

}

}

class OutboxPublisher(private val outbox: TransactionOutbox): EventPublisher {

override fun publish(event: DomainEvent) {

outbox.schedule(RabbitMqSender::class.java).send(event)

}

}

The schedule method leads to the persisting of the task, which involves sending the event to RabbitMQ.

This task is stored in the outbox.

Then, it schedules the execution of this task for after the current transaction has been committed.

This ensures that the event is only sent after the transaction is successfully completed.

In the context of handling potential failures during event sending after a transaction, the TransactionalOutboxScheduler class provides a robust fallback mechanism.

This class periodically executes a run method that continuously calls transactionOutbox.flush().

The flush method in TransactionOutbox is responsible for finding and retrying events that haven’t been successfully executed after a certain amount of time.

It specifically targets events that were initially set up to be executed but haven’t been completed as expected and have not exceeded a predefined number of retry attempts.

This loop continues to invoke flush as long as it returns true, indicating there are events to be processed. Once flush returns false, signifying that there are no more events requiring attention, the loop terminates. This approach ensures that all pending events are addressed promptly.

class TransactionalOutboxScheduler(private val transactionOutbox: TransactionOutbox) {

@Scheduled(fixedDelay = 2000)

fun run() {

while (transactionOutbox.flush()) {

// NOP

}

}

}

To simulate errors in event sending, utilize the /failing-events endpoint.

This endpoint generates a FailingEvent and attempts to send it to RabbitMQ.

The RabbitMqSender is programmed to mimic an error by intentionally failing once for each instance of FailingEvent.

Play around and have fun exploring the outbox pattern!

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of the Transactional Outbox Pattern, it’s evident that this pattern is more than just a technical solution—it’s a strategic approach to ensure data consistency and reliability in the increasingly complex landscape of distributed systems and microservices.

The key takeaway from this discussion is the importance of understanding and adapting to the nuances of distributed systems. The shift from traditional SQL database architectures to distributed models, while challenging, opens up new avenues for building scalable, resilient, and flexible applications. The Transactional Outbox Pattern is a testament to the innovative solutions that emerge when we rethink how data consistency and reliability should be handled in modern application development.

As you implement this pattern in your projects, remember that the journey towards mastering distributed systems is ongoing. The Transactional Outbox Pattern is just one of the many tools in your arsenal, equipping you to tackle the challenges and leverage the opportunities presented by distributed architectures. Stay curious, continue exploring, and most importantly, keep building systems that not only meet today’s demands but are also prepared for tomorrow’s challenges.

References and Further Reading

- Microservices.io - Transactional Outbox Pattern An excellent resource for a concise overview of the pattern and its applications in microservices.

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann: This book offers an in-depth exploration of various patterns and models used in designing modern data-intensive applications, including considerations for consistency and reliability in distributed systems.

- Building Microservices by Sam Newman: A comprehensive guide to designing, building, and maintaining microservices-based applications, with insights into communication patterns and data management in distributed environments.

- Transaction Outbox Library Dive into the source code and documentation of the Transaction Outbox library to understand its implementation and how it facilitates the Transactional Outbox Pattern.